Private Security Sector: historical facts (3/3)

Belgian private security sector #9: Historical facts (3/3)

This ninth chapter focusses on historical drivers (3/3). We will focus on the third step, according to Richard A. K. Lum, « 4 steps to the future »:

What are the causes of these changes? Which category do they belong to? Is there a leading category? Can we deduct a pattern?

This series of publications are extracted from my final paper written within the frame of university certificate on foresight (UCL – Sept 2018)

Causes of changes - Categories

The third step is to identify the causes of these changes or historical drivers.

Historical drivers can be classified into 4 categories

Scientific or technological advancements

Discoveries or tools that have resulted in significant change

Conflict or competition

Political or ideological battles, between states and/or citizens, competition between companies leading to a change in marketing dynamics

New ideas and values

New ideas, philosophies, or concepts that drive and shape change

Chance

Natural disasters, accidents, crises or any other unpredictable event triggering changes in values and attitudes, policies or market structure

Are some drivers dominant, do most of them belong to the same category?

Are we witnessing an established and repetitive or random pattern?

Causes of changes – Application to the security sector

Types | Drivers |

|---|---|

Scientific or technological advancements | Mechanization Use of oil Automotive Electric Lighting Use of social networks |

Conflict or competition | Proliferation in the "guarding" sector Prevailing conflicts in the world War of (dis-) information |

New ideas and values | Consumerism Urbanization Expansion of commercial and industrial sites New forms of crime Indoctrination via social networks Loss of confidence in the police (2) Predominant sense of insecurity (3) Bad reputation of private security (2) Radicalization in prison Appearance of lone wolves " Returnees " |

Chance | Emergence of dictatorships Threats and aggressions towards neighboring countries Rise of Fascism Rise of terrorism Rise of radical Islamism ð Various and multiple extremes (3) (Cyber)terrorist acts |

Other (economic and political) | Economic downturn Change in threat level Increasing threat level of nuclear power plants Fiscal austerity Need for the Public Service to Refocus on its Core Business Assignment of public tasks to the private sector |

With regard to the predominant feeling of insecurity, we refer to Thomas’ theorem: « the behavior of individuals can be explained, not by the reality they are confronted with, but by their perception of it. « If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences »**.

Sources, Useful links & Resources

* Richard A. K. Lum, « 4 steps to the future »

** François Bourse

Executive Master in Foresight – UCL – 2018

Private Security Sector: historical facts (2/3)

Belgian private security sector #8: Historical facts (2/3)

This eighth chapter focusses on historical drivers (2/3). We will focus on the second step, according to Richard A. K. Lum, « 4 steps to the future »:

What happened in the past? Do we witness evolution or revolution in changes? How can we categorize those different changes?

This series of publications are extracted from my final paper written within the frame of university certificate on foresight (UCL – Sept 2018)

Changes identification - Definitions

The second step is to identify changes within the sector or community. Are milestones the result of abrupt changes or the natural result of longer-term evolution?

Practical life

By « practical life », the author understands the rhythm of daily life and the experiences commonly accepted by individuals. We will find here daily practices and procedures, trends – even ephemeral ones, political opinions, …

System

By « system », the author means longer-term structural changes: institutions, regulations and even infrastructures that shape and/or restrict daily life (information technology systems, structure of government agencies, laws, …).

Values

By « values », the author means the views that citizens have about the world, the ways in which groups, communities and societies interpret the world around them, the commonly accepted ideas. It includes all extreme tendencies (« isms »), dominant economic theories, the pursuit of a balanced private/work life. We will therefore complete the title with « public opinions » to avoid any confusion

Changes identification – Application to the security sector

Period | Before 1934 | 1934 - 1990 | 1990-2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

Practical life | Mechanization and use of oil contribute to the Golden Twenties Cars, electric lighting and other facilities are consumed without moderation | Consumerism Urbanisation | Soldiers in the streets (Cyber) Terrorist acts (Dis-) information warfare Change in threat level Increasing threat level of nuclear power plants Social network indoctrination Departures for Syria |

System | Economic downturn Emergence of dictatorships | Expansion of commercial & industrial sites State austerity policy | Austerity for the government Cut budgets Need for the public service to refocus on its "core business" Assignment of public tasks to the private sector New forms of attacks - and new types of security - (cyber) Public Private Partnership (PPP) and partnership between states desired New Issues:

|

Values («public opinions » meaning) | Rise of Fascism (DE - IT) Threats and aggression against neighbouring countries Sense of insecurity | Rise of terrorism Loss of confidence in the police Sense of insecurity Bad reputation of private security | Rise of radical Islamism Loss of confidence in the police Sense of insecurity Bad reputation of private security |

Sources, Useful links & Resources

Richard A. K. Lum, « 4 steps to the future »

Executive Master in Foresight – UCL – 2018

Panelist for Thought Leadership webinar on Security

Panelist for Thought Leadership webinar on Security

The OSPAs, Perpetuity Research and TECAs

”The security sector and the harms caused by Covid-19: what have we learned so far?”

Thursday 27 August 2020 at 15:30 BST

Covid-19 has had a dramatic impact in so many ways. In this webinar we will be examining:

Chair: Martin Gill

Panelists: Matt Hopkins, Anne Wanielista, Thomas Uduo

Private Security Sector: historical facts (1/3)

Belgian private security sector #7: Historical Facts

This seventh chapter focusses on historical drivers (1/3). We will focus on the first step:

What happened in the past? Do we witness recurring schemes? Cycles on-going? Chance roles?

This series of publications are extracted from my final paper written within the frame of university certificate on foresight (UCL – Sept 2018)

Past and drivers

Historical drivers

The method used is taken from Richard A. K. Lum’s « 4 steps to the future »* approach. This is the first step in looking at what happened. This does not augur the future, but potentially could identify :

- recurring patterns

- current cycles

- roles played by chance

and having impacted the present.

First step

First step consists in building the timeline. What events made the headlines? Legislation, wars, crises will be captured.

We have chosen here the regulations relating to private security as milestones and have therefore divided the « past » into 3 periods, each preceding the publication of new legislation.

It is usual to study a period equivalent to the period of anticipation of the future (i.e. 12 years) but here we have preferred to go further back in time in order to verify the repetition or not of the variables and phenomena over a longer period. This is also justified by the fact that technological changes have accelerated and that a period of duration « d » in the future corresponds to a period of longer duration in the past.

This exercise was carried out alone, as were the rest of the steps. For the first stage, in terms of fact-finding, the result is probably close to what we would get with a wider consultation. It is certainly embryonic for the other steps and should therefore be seen as a first illustrative draft that would have to be (in) validated during interviews and/or workshops.

What happened?

1930s: The rise of private fascist milice prompted the legislator to intervene and promulgate the 1934 law banning private milice. There will be two major grievances: the lack of control and punishment.

1980s: the development and growth of private property accessible to the public such as industrial, commercial or leisure centres using private security on the one hand and the rise of terror with the « Brabant killings » on the other hand.

- 1982 – weapons theft + several victims (deaths and injuries)

- 1983 – robbery Delhaize, GB, Colruyt, jewelry shop + theft of bullet-proof vests + several victims (death and injuries)

- 1985 – Delhaize robbery, 28 dead, 22 injured

mobilizing the attention of the police forces on the other hand will form the breeding ground for the 1990 Act on security companies, internal security services and security companies also known as the « Tobback Act », the Home Secretary at the time.

The sector needed to be cleaned up and legitimized, particularly in terms of the morality, training and skills of the people working in it. In addition, the grievances against the law on private milice have been lifted since controls and sanctions are provided for in the new legislation

1990s: the Dutroux criminal case took place in Belgium in 1996. Beyond the victims of course, it dramatically impacted the civil society and had worldwide repercussions. The main protagonist, Marc Dutroux, was convicted and sentenced for raping and murdering young and teenage girls, as well as for paedophilia.

This case showed dysfunctions of justice and police rivalries causing major upheavals and leading to the reform of the police in Belgium. It is not directly linked to private security but with security forces.

Years 2000: Acts of terror are frequent and take various forms, both physical and informational, especially for countries engaged in the fight against jihadism in the Middle East. The feeling of insecurity is present and growing. The confidence of citizens in the police force is undermined. Private security suffers – again and again – from a bad reputation.

Events and historical facts timeline

Sources, Useful links & Resources

* Richard A. K. Lum, « 4 steps to the future »

Executive Master in Foresight – UCL – 2018

Private Security Sector: phenomena

Belgian private security sector #6: Phenomena

This sixth chapter focusses on phenomema definition.

What approaches to identify them, how to define them, what characterize them, and finally, how represent the different levels of uncertainty?

This series of publications are extracted from my final paper written within the frame of university certificate on foresight (UCL – Sept 2018)

Identification of phenomena and key variables

The three approaches favoured by François Bourse are – according to us- relevant for the purposes of our study:

- The literature has already been well exploited

- Retrospective and prospective questionnaires should be used in face-to-face interviews.

- Brainstorming and reflections in sessions or workshops are essential, but it should be noted that the sponsor has doubts about the enthusiasm that these could generate. It will therefore be necessary to emphasize the added value and the « what’s in it for me » for the participants.

A few definitions will clarify the concepts that will recur regularly throughout this work.

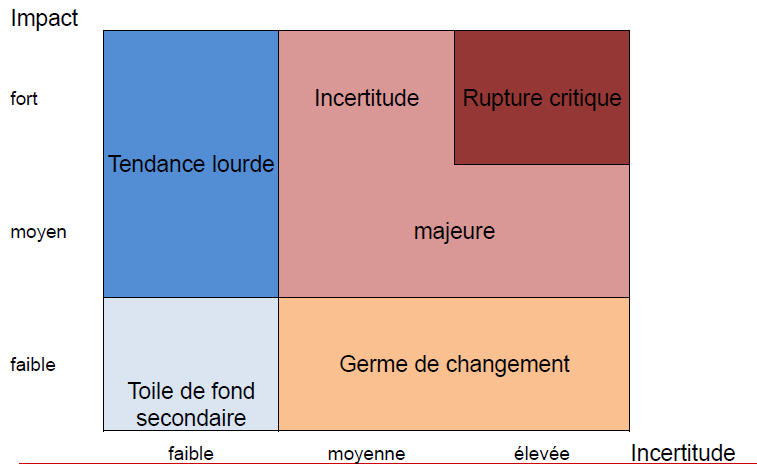

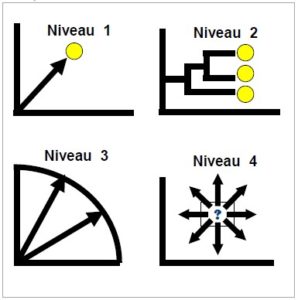

Phenomena definition

By phenomenon, we mean trends, uncertainties, emergences, changes, inertia characterized by impact and uncertainty.

A drawing is worth a thousand words!

Uncertainty

The world is « VUCA », volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous.

« This uncertainty is found in the phenomena identified at the level of:

– the intrinsic characteristics of the phenomenon and its impact…

– Controversies between representations and/or analyses leading to divergent hypotheses of evolution.

– of the more or less well-known nature of the phenomenon » *

These different levels of uncertainty can be seen in the diagram.

Same causes, different effects.

Variable definition

By variable, we mean change factors or drivers. Variables can be external to the system, i.e. exogenous, or internal to the system, i.e. endogenous.

Sources, Useful links & Resources

* Bourse F. (2017). Pratiques Professionnelles de la prospective. CNAM

Executive Master en Prospective – UCL – 2018

Private Security Sector: actors

Belgian private security sector #5: Actors

This fifth chapter focusses on the private security actors.

Who are they, how to identify them, what are their issues and objectives, which ones converge or diverge, what themes do they prioritize on, what are their power relations, and finally, how can we map them in a lobby perspective?

This series of publications are extracted from my final paper written within the frame of university certificate on foresight (UCL – Sept 2018)

Actors

In order not to miss any of them, we decided to list them in different categories:

Those with the money | Those with the knowledge and the ideas | Those in power | The ones with the address book | Those who oppose... or collaborate! |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Business clients of security services | Industry Experts | Legislator | Professional Associations | Competitors |

Leading security companies | Criminologists | Public authorities | Private Associations | Police |

Political parties | Field Officers | Political parties | Political parties | Army |

Private security companies (guarding, services and security systems providers) | Private security companies | |||

Study centres of Political parties | Citizens | |||

Security guards | ||||

Perpetrators of offences or crimes | ||||

Victims of crime or criminal offences | ||||

Political parties |

Political

As far as the actors are concerned, we put the focus on the political aspect. Indeed, political parties are found in all – or almost all – of the categories we have identified.

We decided to look further into the study centres of political parties. Since the sponsor was particularly interested, we developed a « study centre » fact sheet. It seemed interesting to us to define the attitude, the strategic and ideological position and the possible means of action of the parties.

MACTOR : Interactions Method

We opted for the MACTOR method. « The MACTOR method is a method that models the interactions between the different actors of a project or an organization. It stems from the work of Michel Godet in 1990 and aims to define a Matrix of Alliances, Conflicts, Tactics & Objectives between these different actors, as well as the Recommendations that could result from it»[1].

This method consists of 7 phases

1. Actors Identification

It seems to us to be particularly well adapted to the actors of the political world. We have two avenues of application. Indeed, it could apply:

- within the political actors, that is to say by confronting the parties with each other…

- to political parties taken as a whole and comparing them with the other categories of actors identified above

Actor 1 | Actor 2 | Actor 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

Actor 1 | aims and objectives actor 1 | Means of influence of actor 1 on actor 2 | Means of influence of actor 1 on actor 3 |

Actor 2 | Means of influence of actor 2 on actor 1 | aims and objectives actor 2 | Means of influence of actor 2 on actor 3 |

Actor 3 | Means of influence of actor 3 on actor 1 | Means of influence of actor 3 on actor 2 | aims and objectives actor 3 |

Figure: MACTOR Method – step 1. Source: www.lescahiersdelinnovation.com

2. Identification of strategic issues and associated objectives

We took the opportunity to make an actor’s card and, to do so, we have :

- contacted the political parties to identify the study centres in question and, above all, the security experts;

- consulted the existing literature on the subject (charter, website, …)

- Identified the issues and objectives

- compared the results obtained through desk research during face-to-face interviews (whenever possible)

For Belgium, the annual turnover was around EUR 663 million, 90% of which was generated by the 5 largest companies in the sector. Note that in the meantime (Q4 2019), two actors joined forces with the acquisition of Fact Group by Protection Unit.

An actor card will be created for the different parties and their respective study centres.

We will limit ourselves to the political parties with representation in the federal parliament:

- CD&V : Christen Democratisch & Vlaams

- cdH : centre démocrate humaniste

- ECOLO : écologistes confédérés pour l’organisation de luttes originales

- DéFI : démocrate fédéraliste indépendant

- Groen

- MR : Mouvement Réformateur

- N-VA : Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie

- Open VLD : Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten

- PP: Parti Populaire

- Parti Socialiste

- Ptb: Parti du travail de Belgique

- A : Socialistische Partij Anders

- Vlaams Belang

As the MACTOR method generally applies to a number of actors ranging from 10 to 20, we are here in a good average.

To go further

Fact sheets on non-political actors could, of course, be developed at a later stage.

Interested in receiving an example for a political party? Do not hesitate to contact us! We will be more than happy to freely send it.

3. Identification of convergences and divergences

Then, we will create an actors/objectives matrix [1MAO] to see the points of convergence and divergence.

Scoring system :

+1 = actor favourable to the achievement of the objective

0 = neutral actor in relation to the objective

-1 = actor unfavourable to the achievement of the objective

Example (dated Sept 2018):

ACTORS | DéFI | MR | ... |

|---|---|---|---|

OBJECTIVES | |||

Re-establish the authority of the State for a society of trust | +1 | ||

Refuse the privatisation of security missions/tasks | +1 | ||

Defend the exclusive jurisdiction of the police services for any measure of constraint on persons | +1 | ||

Align the budget allocated to Justice with the European average (1.8% GDP) (currently 0.9% GDP) | +1 | ||

Defend community policing as the most effective way to fight crime | +1 | ||

Propose an ambitious plan to invest in new technologies for police forces | +1 | ||

Propose an ambitious plan to invest in new technologies for police forces | +1 | ||

Level the playing field with organized crime | +1 | ||

Create the Federal Intelligence Agency to deploy officers outside the country | +1 | ||

Strengthen the judiciary and the specialized police force | +1 | ||

Prevent the trivialization of violence against representatives by systematically prosecuting it | +1 | ||

Avoid abuse of the use of force by the police (camera wearing) | +1 |

4. Prioritization of convergences and divergences

We will now establish a matrix of the impact of the actors’ objectives on each other.

E.g.: the objective of actor 1 has a strong impact on actor 2.

Scoring system :

0 = the objective has little impact

+/- 1 = the objective of actor « A1 » has consequences on the operating process of actor « A2 ».

5. Assessment of power relations between actors

We will build a matrix of direct influences between actors according to their means of action.

There are, however, limits to the system insofar as these means of action :

– are not always known because there are sensitive information that parties are not always inclined to share…

– are of variable geometry depending on their position in government or in opposition and therefore, at the time the analysis is carried out: in the pre-electoral period (the case at hand) or at the beginning of the term of office

– « incidentally », it is the citizens who will vote …

+/- 4 = the actor « A1 » can question or reinforce the existence of the actor « A2 ».

+/- 3 = the actor « A1 » can question or reinforce the missions of « A2 ».

+/- 2 = actor « A1 » can question or support the projects of actor « A2 ».

+/- 1 = the actor « A1 » can question or reinforce the operating processes of the actor « A2 ».

0 = actor « A1 » has no influence on actor « A2 ».

6. Integration of power relations at the stage of identifying convergences and divergences

Indeed, if one player weighs more heavily than the others (e.g. twice as much), the ratings assigned at this stage should be impacted accordingly (e.g. doubled).

7. Issuing recommendations

Given these power games, we will be able to make recommendations for the future.

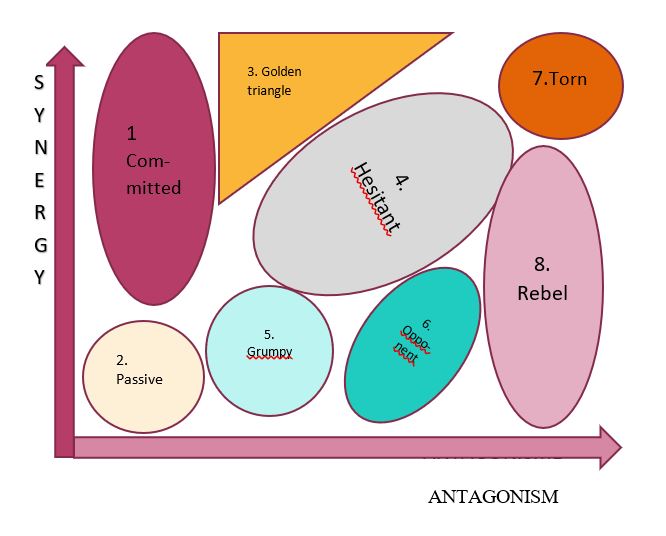

ACTORS' mapping

Finally, as a complement to the MACTOR method, it seems interesting to us, from a lobbying point of view, to map the actors according to their character of favorable or opposed to private security (to the seizing of police tasks, …). They will thus be positioned according to 2 axes: synergy and antagonism.

This exercise could be carried out for all the themes for which decrees have yet to be published. In view of the expected number, it will certainly be necessary to « choose one’s battles ».

To go further

For each category of actors we will look at, we will choose an appropriate method of analysis: MACTOR for political parties PORTER for the analysis of the competitive context (will include private security companies, police, army, ...) …

Sources, Useful links & Resources

[1] Sarr P. (2016). Repéré à https://www.lescahiersdelinnovation.com/2016/02/la-methode-mactor-l-analyse-des-strategies-d-acteurs/

Michel Godet literature

Executive Master en Intelligence Stratégique – HEC-ULg – 2015

Loi du 2 octobre 2017 sur la sécurité privée et particulière

www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/doc/rech_f.htm

Législation codifiée Codex Private Security

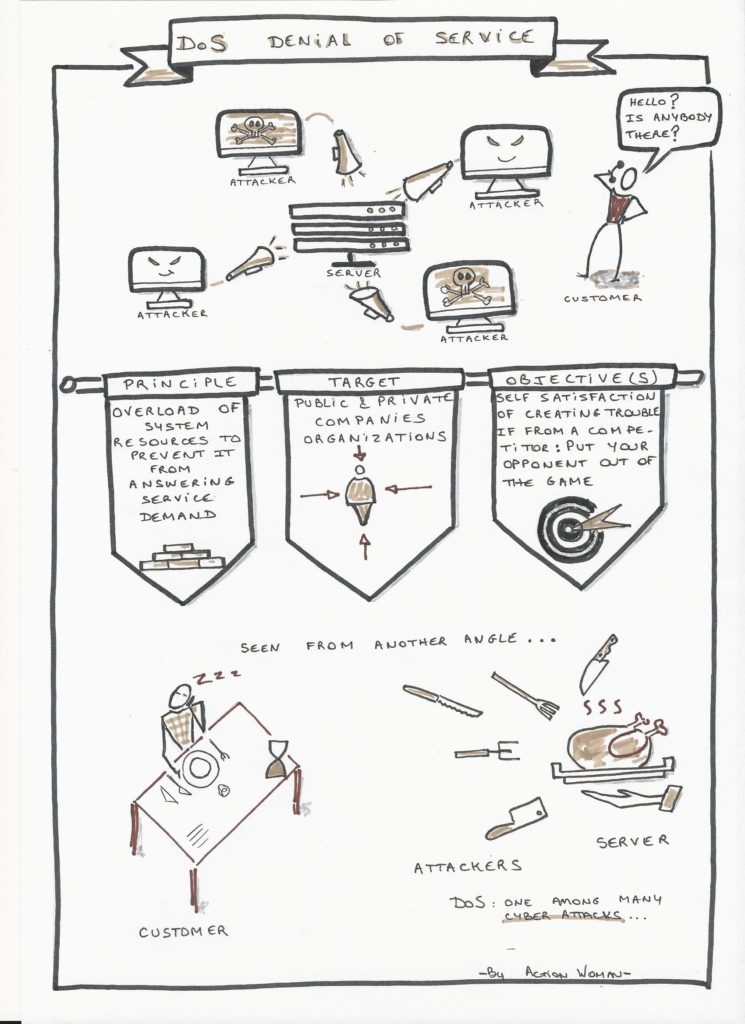

Cyber Attack : Denial of Service

Cyber attack: Denial of Service - DoS

Cyber attacks are numerous and attackers very much creative.

We illustrate hereunder the Denial of Service (DoS) attack.

A picture is worth a thousand words ….

Private Security Sector: market insights

Belgian private security sector #4: Market Insights

This fourth chapter focusses on the private security market insights.

What does the security sector include, what are the activities covered by private security, how does Belgian regulation compare with other countries, what are the figures in Belgium, and finally, what variables can we study in such a foresight analysis ?

This series of publications are extracted from my final paper written within the frame of university certificate on foresight (UCL – Sept 2018)

Security sector

« Private security is opposed to public security and the missions of public services, such as police and inspection services, and also contributes to the prevention of crime »*.

Public security sub-sectors

- Police

- Prison guarding

- « Agent de sécurisation » (new)

- Peacekeeping

- Stewarding (football, rally)

- Army

- General Intelligence Service

- State security

Private security sub-sectors

- Guarding = surveillance and protection of goods and persons

- Security company = supply and installation of equipment for the prevention or detection of crime.

- Private research= investigative work carried out by private investigators

- Security consultancy = advice in the above subjects

As well as

- Public transport security service

- Training organization

Strategy, Business & Regulatory Aspects

« The Comprehensive Security Framework Note (NCSI) constitutes the strategic reference framework for security policy for the period 2016-2019 for all actors who can contribute to it in accordance with their competencies, responsibilities or social objectives”**. It is at the top of the « security tree ». It was published on 7 June 2016 at the suggestion of – at the time – Koen Geens, Minister of Justice, and Jan Jambon, Minister of Security and the Interior.

It is based on several principles:

– Security is a fundamental right

– The integral and integrated approach requires a commitment from all actors in the security chain. In this respect, private security and citizens have a complementary role to play

– It requires monitoring of security phenomena and the threats towards security

The security of citizens being a sovereign mission, the private security sector is a highly regulated sector in Belgium.

The « Tobback » law of 10 April 1990 was replaced by the « Jambon » law of 2 October 2017. Indeed, in almost 25 years, the legislation had been updated 20 times leading in 2014 to a government decision to revised it and, namely, to grant private security companies tasks previously reserved to police***.

The new legislation counts:

- 278 articles

- 45 (royal/ministerial) decrees, some of which not yet published

Nevertheless, there are still many uncertainties for the future.

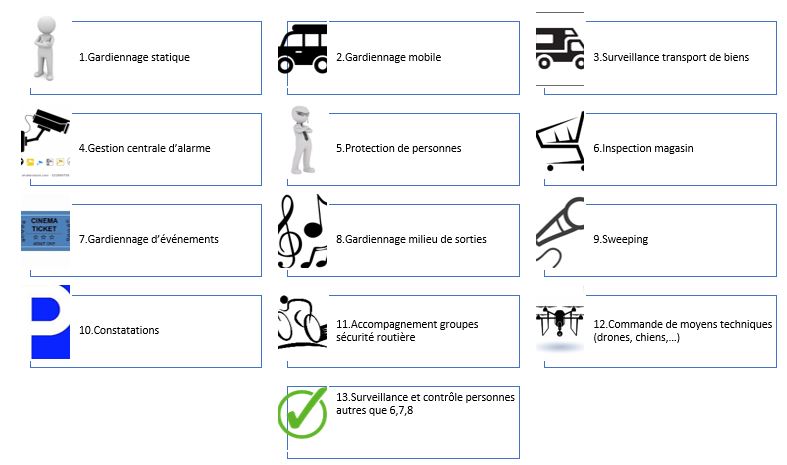

Activities

13 activities are covered, instead of 8 previously.

A distinction is made between mobile and static guarding (+1).

Exceptional transport – which was indeed an exception in the security landscape and probably found itself there because it could not be « accommodated » elsewhere – disappeared (-1).

Technical means are making their appearance, whether to order them (activity 12) or to « chase them away » (activity 9) (+2).

Events, store inspection and dance clubs & alike environments receive specific treatment (+3)

And the surveillance and control of persons is extended (activity 13) (+1).

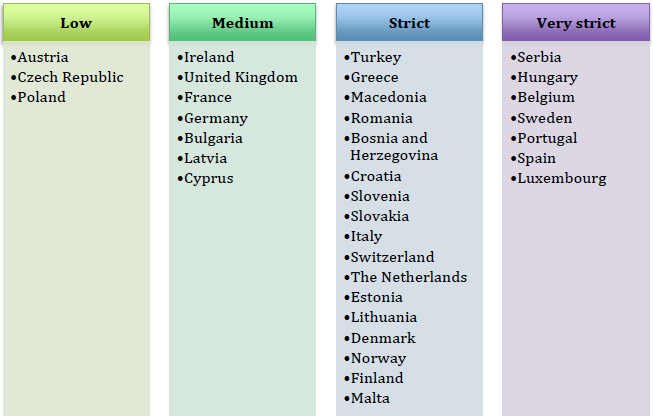

Legislation

For comparison, we refer to the mapping carried out by CoESS on the « strict » nature of the legislation in the various countries under consideration. According to the relative answers to:

- the existence of national legislation

- to the covered activities

- to the requirements

- to admission to the profession

- to penalties

- …

The ranking right next has been established.

The aim here is not to compare the different countries per se but rather :

– on the one hand to corroborate our statement « private security in Belgium is highly regulated »

– on the other hand, to identify a trend at European level, making it possible – or not – to envisage harmonization of legislation in a broader framework than the national one.

In order to keep abreast of the publication of legislative updates, we could of course put a regulatory watch in place, but we have opted for access to the SERIS e-academy platform in order to obtain this information already collected and analyzed by the actor in question.

Figures

In 2017, CoESS has published figures for the private security services sector in Europe.

These figures date from 2015 and concern 34 countries, i.e. the – at the time – 28 member countries of the European Union as well as Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Norway, Switzerland and Turkey.

For Belgium, the annual turnover was around EUR 663 million, 90% of which was generated by the 5 largest companies in the sector. Note that in the meantime (Q4 2019), two actors joined forces with the acquisition of Fact Group by Protection Unit.

PESTEL approach

The PESTEL approach will follow us throughout this exercise, with certain aspects taking precedence depending on the object of the analysis

The focus here is on two aspects:

Economic

- Private security market

- Private security contracts

- Private security companies

- Security guards

Legal

- Legislation on private security

- Controls and sanctions

- Sectoral Agreements

- Entry requirements and restrictions

- Skills

- Use of Weapons and Dogs

- Training

- Public/private cooperation

- Combating piracy on the high seas

These different factors chosen by CoESS can certainly be used as variables or change factors (drivers) and proposed to the panel of experts in order to (in) validate them in the framework of a prospective analysis.

Starting from these variables, we will be able to integrate the phenomena.

We will adopt the approach based on phenomena in our monitoring chapter, since this should help us to identify strong or weak signals and to identify trends.

If the turnover of the private security market is constantly increasing, it should be noted that the profit margin is eroding.

As an illustration, let’s mention the wave of attacks in France at the end of 2015, which triggered a series of increased demand for security guards. Overtime work and emergency recruitment of agents for the same billing has of course had a negative impact on the margin.

Sources, Useful links & Resources

* vigilis.ibz.be

** SPF Justice (7 juin 2016). Résumé de la Note-cadre de Sécurité intégrale, 2016-2019. Seen at https://justice.belgium.be > downloads

*** Accord du gouvernement – 09 October 2014 – Abstract

Loi du 2 octobre 2017 sur la sécurité privée et particulière

www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/doc/rech_f.htm

CCT 89 du 30 janvier 2007 sur les contrôles de sortie

www.cnt-nar.be/cct-liste.htm

Législation codifiée Codex Private Security

Vandormael, D., De Bruyne T. et Verleije S. (2018). La sécurité privée et particulière, approche pratique de la loi. Kalmthout, Belgique : Pelckmans Pro.

CoESS – Confederation of European Security Services

Training « Sécurité, Recyclage personnel dirigeant » – Fact Group – May 2020