Belgian private security sector #4: Market Insights

This fourth chapter focusses on the private security market insights.

What does the security sector include, what are the activities covered by private security, how does Belgian regulation compare with other countries, what are the figures in Belgium, and finally, what variables can we study in such a foresight analysis ?

This series of publications are extracted from my final paper written within the frame of university certificate on foresight (UCL – Sept 2018)

Security sector

« Private security is opposed to public security and the missions of public services, such as police and inspection services, and also contributes to the prevention of crime »*.

Public security sub-sectors

- Police

- Prison guarding

- « Agent de sécurisation » (new)

- Peacekeeping

- Stewarding (football, rally)

- Army

- General Intelligence Service

- State security

Private security sub-sectors

- Guarding = surveillance and protection of goods and persons

- Security company = supply and installation of equipment for the prevention or detection of crime.

- Private research= investigative work carried out by private investigators

- Security consultancy = advice in the above subjects

As well as

- Public transport security service

- Training organization

Strategy, Business & Regulatory Aspects

« The Comprehensive Security Framework Note (NCSI) constitutes the strategic reference framework for security policy for the period 2016-2019 for all actors who can contribute to it in accordance with their competencies, responsibilities or social objectives”**. It is at the top of the « security tree ». It was published on 7 June 2016 at the suggestion of – at the time – Koen Geens, Minister of Justice, and Jan Jambon, Minister of Security and the Interior.

It is based on several principles:

– Security is a fundamental right

– The integral and integrated approach requires a commitment from all actors in the security chain. In this respect, private security and citizens have a complementary role to play

– It requires monitoring of security phenomena and the threats towards security

The security of citizens being a sovereign mission, the private security sector is a highly regulated sector in Belgium.

The « Tobback » law of 10 April 1990 was replaced by the « Jambon » law of 2 October 2017. Indeed, in almost 25 years, the legislation had been updated 20 times leading in 2014 to a government decision to revised it and, namely, to grant private security companies tasks previously reserved to police***.

The new legislation counts:

- 278 articles

- 45 (royal/ministerial) decrees, some of which not yet published

Nevertheless, there are still many uncertainties for the future.

Activities

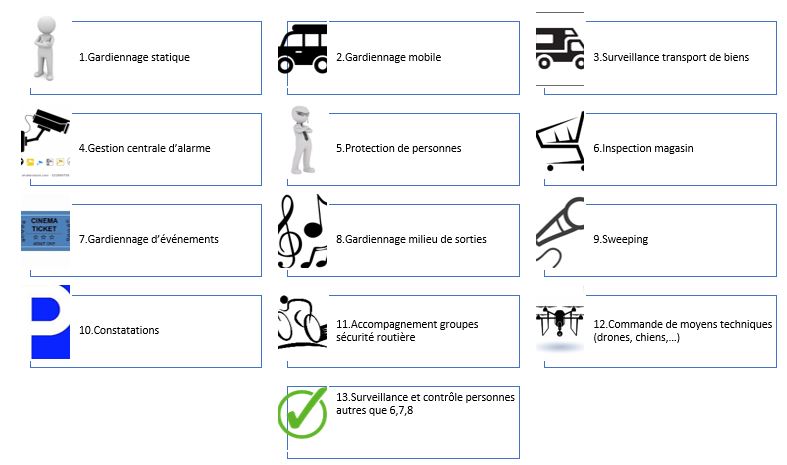

13 activities are covered, instead of 8 previously.

A distinction is made between mobile and static guarding (+1).

Exceptional transport – which was indeed an exception in the security landscape and probably found itself there because it could not be « accommodated » elsewhere – disappeared (-1).

Technical means are making their appearance, whether to order them (activity 12) or to « chase them away » (activity 9) (+2).

Events, store inspection and dance clubs & alike environments receive specific treatment (+3)

And the surveillance and control of persons is extended (activity 13) (+1).

Legislation

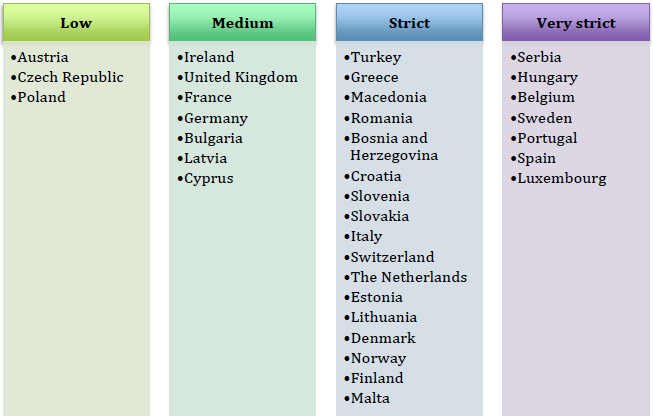

For comparison, we refer to the mapping carried out by CoESS on the « strict » nature of the legislation in the various countries under consideration. According to the relative answers to:

- the existence of national legislation

- to the covered activities

- to the requirements

- to admission to the profession

- to penalties

- …

The ranking right next has been established.

The aim here is not to compare the different countries per se but rather :

– on the one hand to corroborate our statement « private security in Belgium is highly regulated »

– on the other hand, to identify a trend at European level, making it possible – or not – to envisage harmonization of legislation in a broader framework than the national one.

In order to keep abreast of the publication of legislative updates, we could of course put a regulatory watch in place, but we have opted for access to the SERIS e-academy platform in order to obtain this information already collected and analyzed by the actor in question.

Figures

In 2017, CoESS has published figures for the private security services sector in Europe.

These figures date from 2015 and concern 34 countries, i.e. the – at the time – 28 member countries of the European Union as well as Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Norway, Switzerland and Turkey.

For Belgium, the annual turnover was around EUR 663 million, 90% of which was generated by the 5 largest companies in the sector. Note that in the meantime (Q4 2019), two actors joined forces with the acquisition of Fact Group by Protection Unit.

PESTEL approach

The PESTEL approach will follow us throughout this exercise, with certain aspects taking precedence depending on the object of the analysis

The focus here is on two aspects:

Economic

- Private security market

- Private security contracts

- Private security companies

- Security guards

Legal

- Legislation on private security

- Controls and sanctions

- Sectoral Agreements

- Entry requirements and restrictions

- Skills

- Use of Weapons and Dogs

- Training

- Public/private cooperation

- Combating piracy on the high seas

These different factors chosen by CoESS can certainly be used as variables or change factors (drivers) and proposed to the panel of experts in order to (in) validate them in the framework of a prospective analysis.

Starting from these variables, we will be able to integrate the phenomena.

We will adopt the approach based on phenomena in our monitoring chapter, since this should help us to identify strong or weak signals and to identify trends.

If the turnover of the private security market is constantly increasing, it should be noted that the profit margin is eroding.

As an illustration, let’s mention the wave of attacks in France at the end of 2015, which triggered a series of increased demand for security guards. Overtime work and emergency recruitment of agents for the same billing has of course had a negative impact on the margin.

Sources, Useful links & Resources

* vigilis.ibz.be

** SPF Justice (7 juin 2016). Résumé de la Note-cadre de Sécurité intégrale, 2016-2019. Seen at https://justice.belgium.be > downloads

*** Accord du gouvernement – 09 October 2014 – Abstract

Loi du 2 octobre 2017 sur la sécurité privée et particulière

www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/doc/rech_f.htm

CCT 89 du 30 janvier 2007 sur les contrôles de sortie

www.cnt-nar.be/cct-liste.htm

Législation codifiée Codex Private Security

Vandormael, D., De Bruyne T. et Verleije S. (2018). La sécurité privée et particulière, approche pratique de la loi. Kalmthout, Belgique : Pelckmans Pro.

CoESS – Confederation of European Security Services

Training « Sécurité, Recyclage personnel dirigeant » – Fact Group – May 2020